How does one begin at the beginning when the story feels like a fractal? I suppose all stories are this way, for as long as human memory extends there was always a Before. Perhaps this quandary is important to me because my current work exists as a record of a liminal space, made in and of a time of becoming something, someone, new. My work contains echoes and fossils and ashes of The Before, it is the process of creating realized dreams that sustained me when dreams were all I had, it is the unfolding of discovery like new dawn—a growing and shifting light revealing itself in fleeting moments as my horizons expand.

The Before, as it relates to my work, was my life before the amputation of my left foot. It was years defined by the intense pain of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome that had collapsed my world like a black hole. It was years where my primary source of human interaction was as a patient, a medicalized object. I seldom left my home for anything other than medical appointments or absolute necessity; I didn’t have the capacity to read or watch movies so even characters were outside of my aloneness. I sat at my window and watched the New Mexico sky, the birds, the seasons, the mountains. In the Before, pain stretched moments into eternities, and I looked to the mountains for their understanding of geologic time. I watched the slow changes in the earth outside my window, a canyon full of Juniper trees and prickly pear cactus. I watched day by day as the wind and the animals and the occasional desert mountain rains left their marks, moved the sand and soil almost imperceptibly. Or perhaps it wasn’t that it was imperceptible, but that the changes only bore noticing when I sat so still and looked for so long.

How do I tell you the story of who I am becoming without returning to the event horizon?

I am not sure I have an answer to that question yet, but the asking of it made me realize, in a new way, why I have been living at light speed since waking up from surgery: more than “making up for lost time” I have been living to outrun the blackhole that consumed my life for three years. I woke up out of pain and immediately charged towards life, happiness, love, adventure, excitement, and doing. I traveled, I tried surfing and paddleboarding and skydiving. I fell in love with the most incredible woman. I made my return to the hotshop and started blowing glass again. I applied to graduate school and moved to Canada to start within a week of my acceptance. I saw the northern lights for the first time, waded in a glacial lake, and got to know my way around a new city.

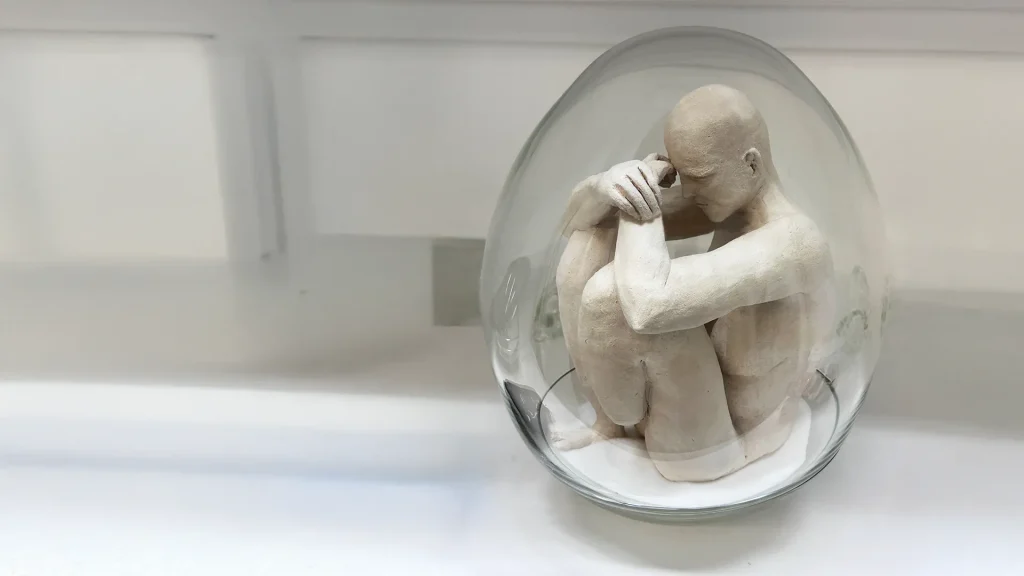

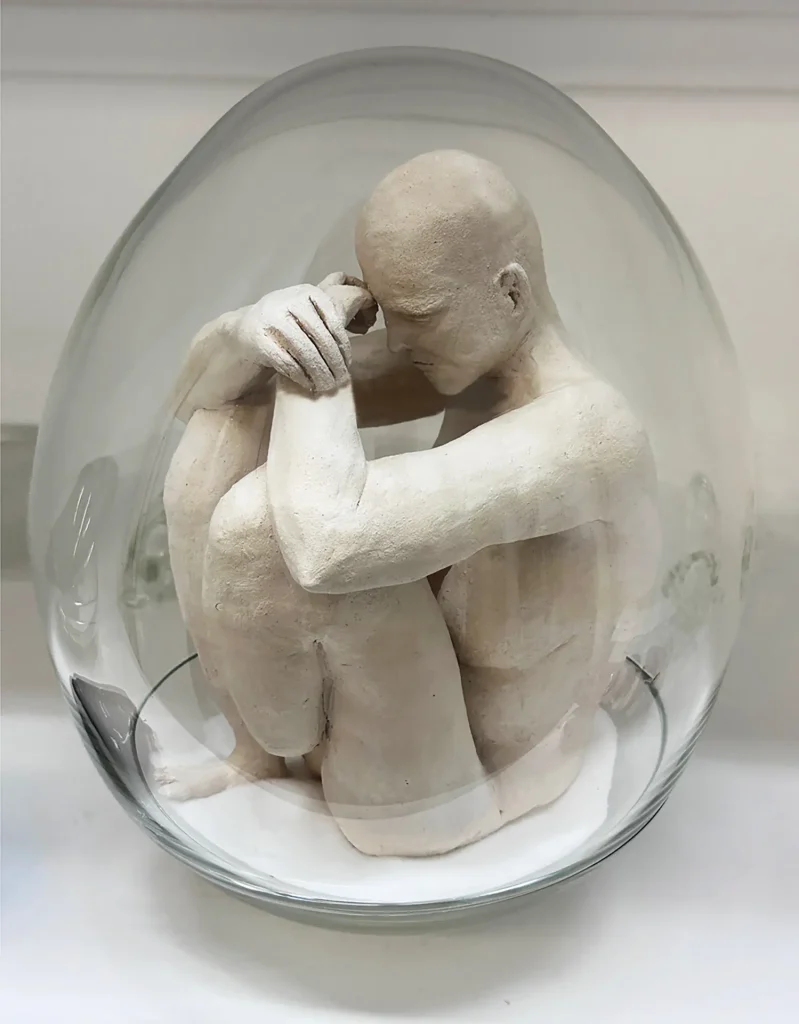

The first few months were smooth sailing. I learned what it was like to live in my body again—to safely inhabit my skin, to sleep, to enjoy rather than endure, to anchor my experience to my physical being. I thought, in my rampant joy and full-hearted enthusiasm, that my work would be exultant, triumphant. I only wanted to look forward and create the future I am now free to believe in. In September, I got Covid for the first time. After two weeks in bed, I wore my prosthetic to school. I got home after a very long day and peeled back the layers of socks and liner to discover that my scar had turned black—a color I hadn’t seen on my skin since the necrosis that led to my amputation. Fear closed in around me, echoes of The Before ringing in my head. The air felt thick and hard to breathe, like the unknowingness trapped me in an amniotic moment. Shelled stasis, the shape of fear—I knew that the moment of knowing, regardless of what I came to know, would shatter it, would release me.

As it went, it was less dramatic than that. It was a series of long slow sighs as I remembered how to breathe. It was learning that my scar had infused itself with melanin, which is a healing compound in the skin, after I had over-taxed the tissue my body had knitted itself back together with. It was tentatively trusting my body not to betray me again. It was acknowledging that triumph isn’t a singular moment, that this is a story that will detour and harmonize and be as complicated and messy as it is beautiful. Frustratingly, healing is not a linear journey. Fortunately, setbacks, unexpected turns, and moments of necessary rest provide opportunities for me to explore more deeply the meaning and experience of the liminality of becoming.

As I made my return to the hotshop, visions of a large scale, complex, sculpted glass phoenix rising in triumph danced in my mind. She has been there, rising from the ashes of my foot, since before I even had a date for the surgery—the beacon of a future I could believe in. Yet, as I began to make things, none of them belonged to the phoenix exactly. The phoenix felt too big of a place to start and, as I recovered from the combined effects of covid and the first set back, like it would have been a presumptive triumph rather than true to my experience. Instead, I found myself making glass body parts—initially as part of plans for a glass self-portrait marionette.

I started with a hand, figuring it was important to set the scale by the smallest I could manage a complex form like the hand—small because I anticipate the weight of a fully articulated glass marionette will be a challenge to puppet. When I had success with the hand, I decided to take on the left foot, knowing that as a self-representational object, taking on my amputated foot would be among the most emotionally loaded to tackle. I am sculpting these parts hollow, so took a gather and breathed into the pipe to inflate the glass. Using various hand tools, I slowly pushed and pulled the bubble into the shape of a foot. As I worked, adding heat with my torch to specific parts as I shaped toes, the arch, the heel, occasionally adding a puff of air to add volume from the inside, I felt a resonance with the material. I reheated the glass in the glory hole and watched as a thin spot in the glass melted open leaving a hole in the ball of the foot. Had I been sculpting any other foot this might have been cause for frustration. But as the small hole opened, I watched in awe. It was in the exact location that my left foot had worn holes in every sock from the time I was twelve and learned to walk for the second time. After the injury that had resulted in CRPS the muscles in my foot had remained contracted, pulling the first bone in my second toe vertical and causing a pressure point in the ball of my foot, in exactly the place the glass wore through and melted away in the heat. There was suddenly no question that the glass knew that this was my foot, not just any foot. This is part of the magic of this material: it is responsive, it intuits and understands things I don’t even know I am communicating to it. It is animated by energy, filled with breath, it reacts to touch, it communicates and resists and together we dance things into being.